In July last year, the SRA published a report by the Bridge Group highlighting the diversity challenges around solicitor admission. This report challenged the SRA to gather and make available data relating to diversity and inclusion as the SQE is rolled out over the coming years.

The Central Applications Board (CAB) 2020 annual report on the 15,000 plus candidates applying for the GDL and LPC courses currently required for solicitor admission, further underlines the scale of the diversity and inclusion admissions challenge that the SQE is being expected to tackle. These statistics show that diversity issues emerge even as candidates start their journey to qualification.

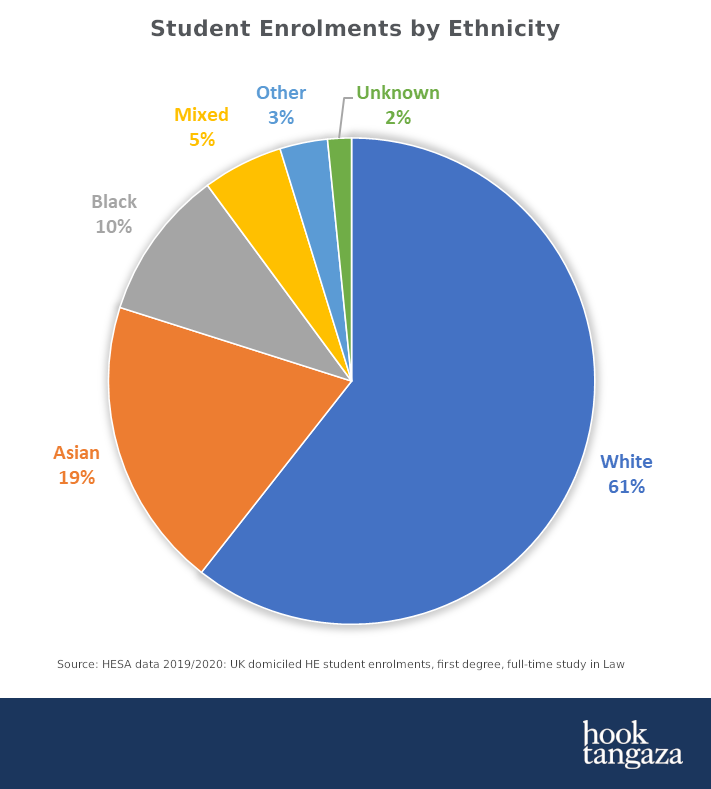

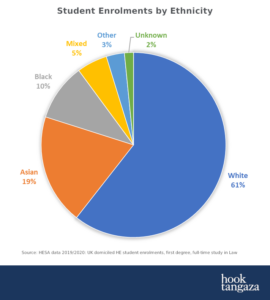

If we focus just on ethnicity, there has long been a concern about the post qualification experience of Asian, Black, mixed and other ethnic minorities in the legal sector. Although statistics from the Higher Education Statistics Authority (HESA) indicate that non-White students represent nearly 40% of those enrolling in law degrees and SRA data suggests that non-White solicitors make up 21% of the profession, only 8% of partners at the largest law firms are non-White. In other words, there is an underrepresentation of ethnic minority solicitors in the highest paying end of the legal market. CAB data on GDL and LPC enrolments gives us some insights into why that might be, as well as helping to explain why many non-White candidates do not qualify after obtaining a law degree, or dropout during further study.

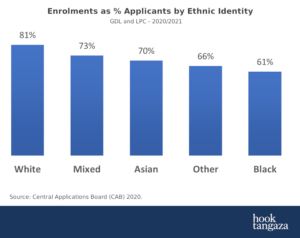

Firstly, the proportion of non-White candidates applying for a GDL or LPC course who do not subsequently enrol is consistently lower than the proportion of White applicants who decide not to proceed with their legal studies having first applied.

According to CAB’s data, white applicants were 20% more likely to receive an offer and enrol on GDL and LPC courses than Black applicants. The reason for this can perhaps be found in the data collected by CAB about the funding of these studies.

The vast majority of applicants who enter the profession with a non-law degree will have to pay for their own law conversion course, but for the 20% or so who obtain funding, nearly all (89%) will have attended a Russell Group university. So, if you are a candidate with a sociology degree from a Metropolitan university who knew no lawyers growing up and who needed encouragement to see the law as a career option, you are more likely to have to pay for your studies than someone who studied History of Art at Cambridge University. Regrettably, non-White candidates are more likely to fall into the former than the latter category.

Funding matters because those without it are less likely to enrol, more likely to drop out during their course and more likely to underperform in terms of their results. On the other side, they come out with higher levels of student debt and lower longer-term earning potential within the legal sector.

Funding also determines the long-term diversity structure of the profession. Candidates from lower socio-economic backgrounds, who are statistically less likely to have studied at Russell Group universities, and who are also likely to be disproportionately from minority ethnic backgrounds, are in turn less likely to have the opportunity to be hired and sponsored through their LPC by a top corporate firm.

So the seeds of the legal sector’s diversity problems are sown very early on, in campus visits and milk round recruitment focused on Russell Group universities. Can the SQE help? Maybe, to some extent. The new system will reduce the cost of qualification to non-funded applicants but unless firms broaden their recruitment policies, there will continue to be a structural underrepresentation of individuals from lower socio-economic groups and certain minority ethnic backgrounds. A more transparent and efficient marketplace for early-stage recruitment would undoubtedly help, but the SQE alone cannot produce this.

Perhaps a bigger issue, which should concern us all, is that it is the solicitors who will one day work in criminal law, family law and in helping the most vulnerable in society, who will continue to pay for the privilege of entering the profession. The SQE might reduce the debt they carry into their careers to some extent, but they are likely to find that they increasingly have to self-manage their own work experience journey in order to qualify, whilst those at the corporate end of the market receive free quality training. The “levelling up” agenda needs to reach the providers of legal services as well as the recipients.